Copy link

Surgical Fires

Last updated: 02/15/2023

Key Points

- Surgical fires can result in devastating injuries and are preventable.

- All components of the surgical fire triangle must be present for a surgical fire.

- Open oxygen delivery must be avoided in procedures above the xiphoid process.

- A surgical fire risk assessment must be performed during the surgical time out.

Introduction

- Surgical fires are fires that occur in, on, or around a patient while undergoing a surgical or medical procedure.1,2 Based on data extrapolated from Pennsylvania, it is estimated that approximately 600 surgical fires occur in the United States every year.1 With underreporting of cases, the true incidence is probably higher.

- Surgical fires are “never” events and can be prevented.

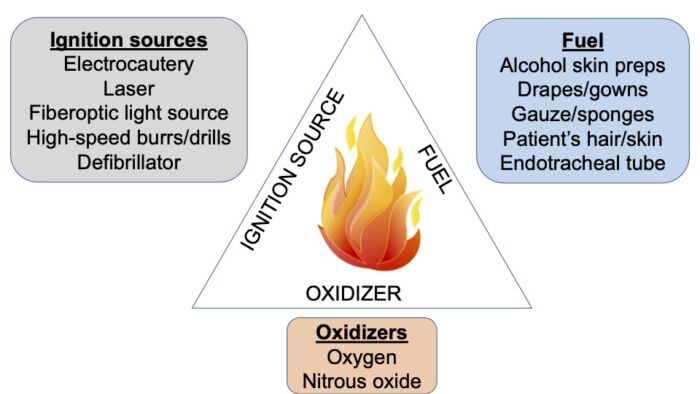

Surgical Fire Triangle

- The basic elements of the fire triangle are ignition source, oxidizer, and fuel source.1-4 A fire occurs when all the elements of the fire triangle come together in the right proportions and under the right conditions. Different members of the surgical team are primarily involved with different sides of the triangle.

Figure 1. Surgical fire triangle

- An oxygen-enriched atmosphere (OEA) exists when the oxygen concentration exceeds 21%. OEA is involved in most surgical fires, and it lowers the temperature and energy at which a fuel will ignite.1 OEA fires are hotter, burn more vigorously, and spread more rapidly.

- According to ASA Closed Claims data, 85% of surgical fires occurred in the head, neck, or upper chest, and 81% of cases were under monitored anesthesia care.5 Open O2 delivery and configuration of surgical drapes can result in an OEA, increasing the risk of surgical fires.

- N2O also supports combustion. Fires involving N2O are as severe as OEA fires.

Prevention of Surgical Fires

Managing Oxidizer1-4

During head, neck, face, and upper chest surgery:

- If the patient can maintain safe SpO2 without supplemental O2, consider using air for open delivery. If not, consider securing the airway with a supraglottic airway or ETT.

- If open O2 delivery is used, deliver the minimum O2 concentration necessary for adequate oxygenation. Begin with O2 concentration < 30% and increase if necessary. If using > 30% O2, deliver 5-10 L/min of air under the drapes to wash out excess O2.

- Stop supplemental O2 for at least one minute before using electrosurgical cautery.

Managing Ignition Source1-4

When using an electrosurgical cautery, laser, or fiberoptic light source:

- notify surgeon of the presence of OEA;

- activate unit only when the tip is in view;

- deactivate unit before the tip leaves the surgical site;

- place unit in a holster when not in active use;

- do not use electrocautery to enter the trachea;

- do not use red rubber catheters to sheathe long electrocautery probes;

- place laser on stand-by mode when not in active use;

- turn off fiberoptic light source when not in use;

- do not allow fiberoptic light source to come in contact with fuel (drapes/gauze).

Managing Fuel1-4

- Use nonalcohol-based skin preps (Povidone-Iodine), if possible

- With alcohol-based skin preps, avoid pooling of prep

- Allow prep to fully dry (at least 3 minutes) before draping

- Remove towels used to catch dripped flammable prep before draping

- Moisten sponges when used in proximity to ignition source

- When using laser for airway surgery, consider using laser resistant ETT, if appropriate. Use saline in the cuff to prevent cuff ignition and consider using dye in cuff to indicate puncture.

Fire Risk Assessment1-4

- Open communication between operating room (OR) team members is crucial for the prevention and management of surgical fires.

- During the surgical time-out, a fire risk assessment must be performed to assess fire risk, develop a strategy to prevent fires, designate roles for team members in the event of a fire.

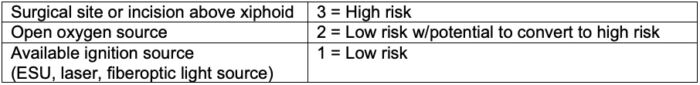

- The Silverstein fire assessment tool assigns one point for each risk factor present and stratifies the risk based on the total score.6

Table 1. Fire Risk Assessment

- High-risk surgeries include2

- Tonsillectomy

- Tracheostomy

- Laryngeal papilloma removal

- Cataract surgery

- Burr hole surgery

- Removal of lesions from head, neck, or face

Management of Surgical Fires

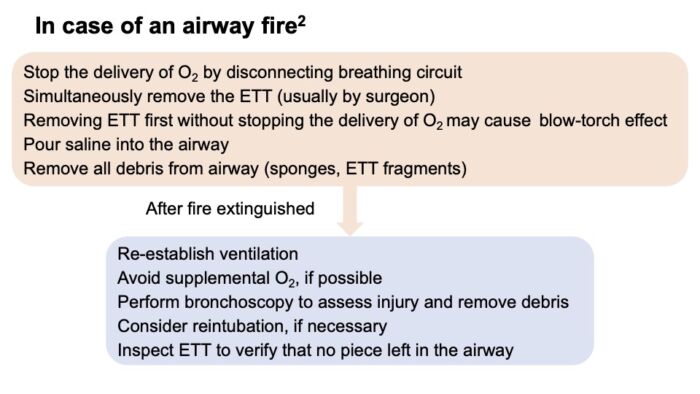

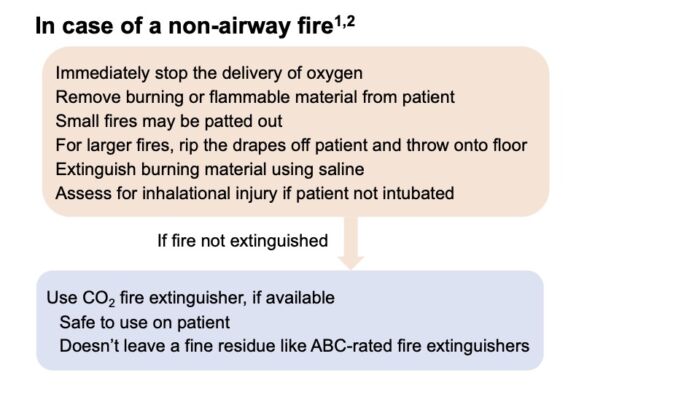

- When early warning signs of a surgical fire such as flame or flash, unusual sounds, odors, or smoke are noted, immediately inform the team and halt the procedure.

Figure 2. Airway Fire

Figure 3. Nonairway Fire

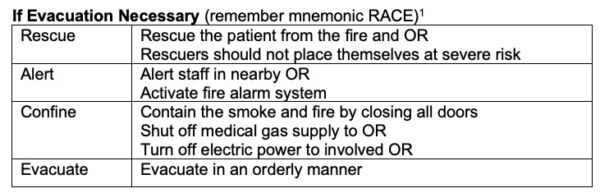

Table 2. Evacuation

References

- ECRI Institute. New clinical guide to surgical fire prevention. Patients can catch fire- here’s how to keep them safer. Health Devices. 2009; 38:314-32. PubMed

- Apfelbaum JL, et al. Practice advisory for the prevention and management of operating room fires: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Operating Room Fires. Anesthesiology 2013;118(2): 271-90. PubMed

- Cowles Jr CE, Culp Jr WC. Prevention of and response to surgical fires. BJA Education. 2019;19(8): 261-66. PubMed

- Jones TS, Black IH, Robinson TN, et al. Operating room fires. Anesthesiology 2019;130- 492-501. PubMed

- Mehta SP, Bhananker SM, Posner KL, et al. Operating room fires: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology. 2013; 118:1133-39. PubMed

- Mathias JM. Scoring fire risk for surgical patients. OR Manager. 2006: 22: 19-20. Link

Other References

- Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. Operating Room Fire Safety Video. Prevention and Management of Operating Room Fires Video. Published February 2010. Accessed February 15, 2023. Link

- ECRI. Surgical Fire Prevention. Accessed February 15, 2023. Link

- Chatterjee D. Surgical Fires: Prevention and Management. OpenAnesthesia. Published November 18, 2018. Accessed February 15, 2023. Link

- Ward P. Airway fires. Anaesthesia Tutorial of the Week. WFSA. Published May 16, 2017. Accessed February 15, 2023. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.