Copy link

Electroconvulsive Therapy Anesthetic Considerations

Last updated: 01/04/2023

Key Points

- Most healthy patients will not require any intervention for transient increases in blood pressure and heart rate. However, management of hypertension and tachycardia with intravenous (IV) β-blockers or other agents may be necessary in patients at risk for cardiac ischemia.1

- Postictal agitation may be effectively managed with additional sedation and prevented at subsequent treatments by preemptive use of such medications.1

- Modern cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIED) are extremely resistant to the effects of electromagnetic interference (EMI) but may still become damaged or unintentionally reprogrammed under certain circumstances.2

Premedication

- Headache is the most commonly reported complaint after electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), occurring in roughly 50% of patients, and is usually treated prophylactically with ketorolac 30mg and/or acetaminophen.

- Nausea after ECT may occur in up to 25% of patients and is usually treated prophylactically with ondansetron 4 milligrams, administered prior to induction of anesthesia.

- For patients at risk for bradycardia during treatment, IV glycopyrrolate 0.2 milligrams may be administered immediately before ECT.

- For patients with copious oral secretions, IV glycopyrrolate should be administered at least 20 minutes before ECT treatment, to allow oropharyngeal secretions to be dried up.

- Beta-blockers and other antihypertensive agents have the potential to interfere with the generation of the therapeutic seizure but may be indicated in some cases.

Anesthetic Agents

- Since all general anesthetics have the potential to interfere with the generation of the therapeutic seizure, the choice of anesthetic and dose must be tailored to the individual needs of each patient.1

- Common medications used to induce anesthesia for ECT include:

- Methohexital:

- It is an ultrashort-acting barbiturate with kinetics similar to propofol.

- Currently, the induction agent of choice due to low anticonvulsant properties

- Propofol:

- Ideal kinetic profile but significant anticonvulsant properties may result in shorter seizures

- Ideal for patients with a low seizure threshold or history of postictal agitation

- Ketamine:

- N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist that may enhance seizures

- A reasonable choice for patients with an elevated seizure threshold

- Also has intrinsic antidepressant properties3

- Etomidate:

- Kinetics similar to propofol and methohexital with minimal effects on seizure threshold and safer cardiovascular risk profile

- Agent of choice in the hemodynamically unstable patient

- Theoretical risk for adrenal suppression with repeated exposure4

- Ketofol:

- It is a combination of 2.5mg ketamine per milligram of propofol.

- With simultaneous administration, less of each agent is required to induce anesthesia.

- The lower dose of propofol reduces the anticonvulsant impact, and the addition of ketamine may be associated with greater antidepressant effect.

- Remifentanil:

- Pharmacokinetics are ideal for use in ECT.

- Typically used because of its low anticonvulsant properties for patients in whom it is difficult to induce an acceptable seizure

- It should be combined with low-dose hypnotic to avoid awareness.

- Inhalational Agents:

- Indicated for patients who don’t tolerate IV insertion because of severe needle phobia, severe psychosis, or agitation, or for patients who don’t tolerate IV induction because of the pain associated with injection

- Methohexital:

Figure 1a (left). Choosing the most appropriate anesthetic agent at the lowest effective dose requires (1b, right) close collaboration between the anesthesiologist and ECT psychiatrist.

Posttreatment Management and Special Situations

- Postictal Agitation: Although most individuals tolerate ECT well, approximately 10% of patients develop transient emergence agitation, typically characterized by restlessness, confusion, and delirium which responds to:

- behavioral interventions (gravitational restraint, distraction, verbal reorientation);

- benzodiazepine (e.g., midazolam 1–2 mg IV);

- antipsychotic medications (e.g., droperidol 1 mg IV);

- a small bolus dose of propofol (e.g., 30 mg IV).

- Pulmonary Edema: Although very rare, pulmonary edema after ECT has been reported. Etiologies include:

- flash pulmonary edema secondary to a hypertensive crisis;

- negative pressure pulmonary edema;

- cardiogenic pulmonary edema;

- asthma treated with clenbuterol hydrochloride.

- Febrile Reactions: Extremely rare complications include malignant hyperthermia and febrile reactions unrelated to malignant hyperthermia.

- Neurologic Dysfunction: Focal neurologic dysfunction immediately after ECT is rare but may result from:

- cerebrovascular ischemia;

- ruptured aneurysm;

- transient electrophysiologic dysfunction (Todd’s paralysis).

- Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy: This is a reversible stress-induced cardiomyopathy characterized by left ventricular hypokinesis and apical ballooning triggered by severe physical or emotional stress, or medical procedures including ECT.

ECT in Patients with Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices (CIED)

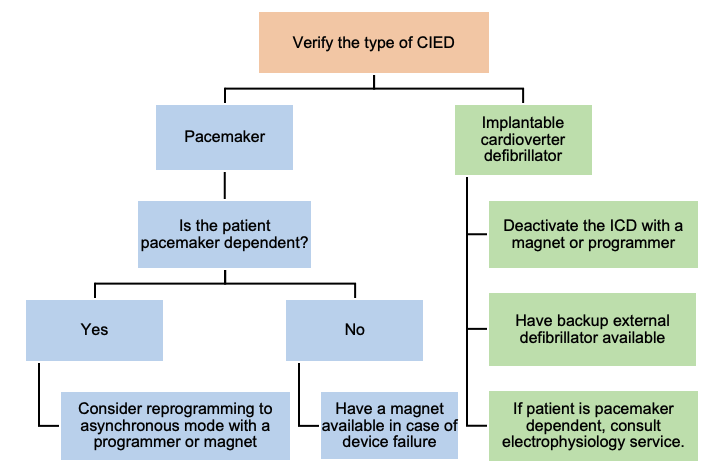

Most patients with cardiac pacemakers or other implanted devices can be safely treated. Management of these patients should focus on maintaining proper device function (Figure 3).

- Minimize electromagnetic interference (EMI) by placing the ECT stimulus and the peripheral nerve monitor at least 15 cm away from the CIED.

- The most likely source of EMI is from the movement due to fasciculations or a poor block.

- Clinicians should consider using an increased dose of succinylcholine in patients with CIEDs.

- Potential adverse outcomes from the CIED include:5

- physical damage to the device or lead;

- lead fracture or repositioning resulting in device failure;

- inadvertent reprogramming;

- inappropriate discharge of an ICD;

- inadvertent reset to backup mode.

Figure 2. Algorithm for management of a patient with CIED during ECT. Adapted from Bryson EO, et al. Individualized Anesthetic Management for Patients Undergoing Electroconvulsive Therapy: A Review of Current Practice. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(6):1943-56.

References

- Bryson EO, Aloysi AS, Farber KG, Kellner CH. Individualized Anesthetic Management for Patients Undergoing Electroconvulsive Therapy: A Review of Current Practice. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(6):1943-56. PubMed

- The American Society of Anesthesiologists Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters. Practice advisory for the perioperative management of patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices: pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Anesthesiology. 2011; 114:247–61. PubMed

- Kranaster L, Kammerer-Ciernioch J, Hoyer C, Sartorius A. Clinically favourable effects of ketamine as an anaesthetic for electroconvulsive therapy: a retrospective study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011; 261:575–82. PubMed

- Zed PJ, Abu-Laban RB, Harrison DW. Intubating conditions and hemodynamic effects of etomidate for rapid sequence intubation in the emergency department: an observational cohort study. Acad Emerg Med. 2006; 13:378–83. PubMed

- Stone ME, Salter B, Fischer A. Perioperative management of patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices. BJA. 2011;107: i16–i26. PubMed

Other References

- Bryson EO. Electroconvulsive Therapy Procedure. OpenAnesthesia. Published January 4, 2023. Accessed February 6, 2023. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.