Copy link

Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections

Last updated: 03/14/2024

Key Points

- Catheter-related bloodstream infections (CRBSI) are primarily associated with central venous catheters or arterial lines, though all intravascular devices present an infection risk.

- Key risk factors include catheter type, duration of catheterization, and the clinician’s skills in inserting the catheter.

- The most common pathogens causing CRBSIs include coagulase-negative staphylococci, S. aureus, enterococci, and Candida species.

- Clinical features of CRBSIs often include fever or chills, with severe cases leading to complications like sepsis, endocarditis, or septic arthritis.

- Treatment strategies include empirical antibiotics, with vancomycin for all patients, and specific antibiotics based on identified pathogens.

- Prevention focuses on proper hand hygiene, use of sterile equipment, and site-specific insertion practices, including the use of chlorhexidine for skin antisepsis.

Introduction and Pathogenesis

- CRBSI is a common cause of morbidity and mortality for patients during their hospital stay. In the United States, 80,000 episodes of central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) are diagnosed annually and are associated with increased mortality and elevated economic costs (39,000 US dollars per episode).1

- The terms CRBSI and CLABSI have small differences between the two but are often used interchangeably in hospitals. For this summary, we will use the term CRBSI when referring to both scenarios.

- CRBSI are primary bloodstream infections that are typically caused by the placement of a central venous catheter or arterial line. CRBSI are less likely caused by peripheral venous access; however, all intravascular devices confer some level of risk of infection.1

- One critical factor enhancing the likelihood of a microorganism’s pathogenicity is its ability to colonize the skin and establish biofilms. The microorganisms can migrate to the catheter site and eventually stick onto the sheath inside the catheter and multiply in the bloodstream.

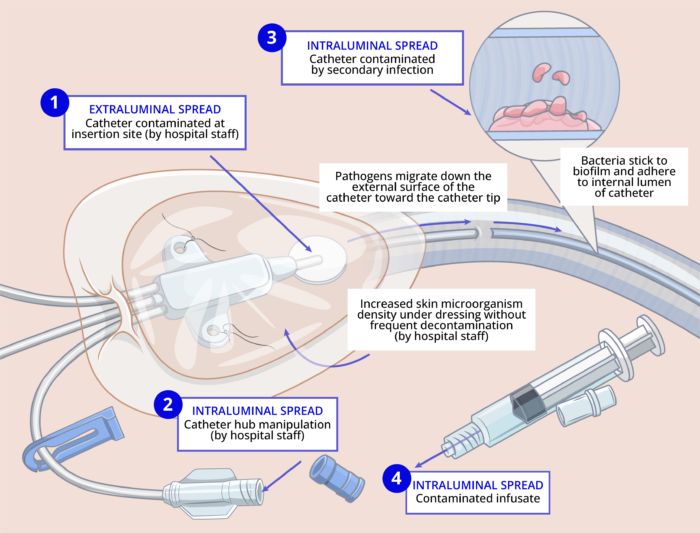

- The common routes for catheter contamination are as follows2: (Figure 1)

- Insertion site contamination: Skin pathogens enter the cutaneous catheter tract and migrate toward the catheter tip. This most commonly happens within the first 7 days of catheter insertion and is thought to occur at the time of insertion. Insertion site contamination can also occur if the catheter site is not decontaminated frequently, and as a result, skin microorganism density can increase under the dressing.

- Intraluminal contamination can occur when the catheter hub is manipulated and pathogens gain access to the intraluminal surface of the device, where they become incorporated into biofilm, allowing sustained infection and hematogenous spread. This typically happens more than 7 days after catheter insertion.

- Catheter contamination can occur by secondary bloodstream infection from another source (e.g., pneumonia or urinary tract infection).

- Rarely, a contaminated infusate can infect the catheter.

Figure 1. The pathogenesis of CRBS. Adapted from O’Grady NP. Prevention of central line–associated bloodstream infections. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(12):1121-31.

Risk Factors and Protective Factors3

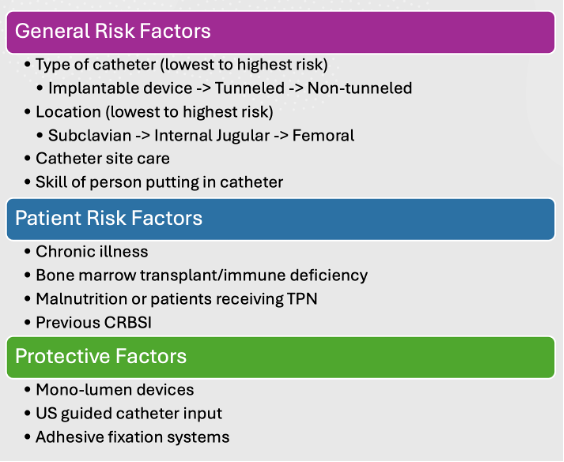

- The risk factors and protective factors for CRBSI are listed in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Risk factors and protective factors for CRBSI

Common Pathogens

Common microbial causes of CRBSI are listed below.3,4

- Coagulase-negative staphylococci – 16.4 percent

- Enterococci – 15.2 percent

- S. aureus – 13.2 percent

- Candida species – 13.3 percent

- Klebsiella species – 8.4 percent

- Escherichia coli – 5.4 percent

- Enterobacter species – 4.4 percent

- Pseudomonas species – 4 percent

Clinical Features

- The most common clinical feature of CRBSI is fever and/or chills.3

- Any patient with fever or chills for an undisclosed reason with a central venous catheter in place should be further investigated.

- The presence of erythema, pain, or swelling should raise suspicion for CRBSI.

- Most patients do not have any purulence at the insertion site.

- Less common manifestations include altered mental status, hemodynamic instability, and signs of sepsis (hypothermia, hypotension, acidosis, etc.).

- Complications of CRBSI include endocarditis, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, or thrombophlebitis.

Diagnosis

- Two sets of blood cultures should be obtained from peripheral sites before initiation of antibiotic therapy and after exclusion of alternative sources of infection. Either two separate venipuncture samples or one sample from the catheter lumen and another sample from the peripheral venipuncture can be obtained3

- For the diagnosis to be confirmed, both cultures must grow the same organism.

- Patients should also receive additional laboratory tests like complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic profile, and inflammatory markers similar to sepsis workup.

Management

Catheter Removal or Salvage5

- Patients with suspected bloodstream infections should be treated empirically with antibiotics and potentially have the catheter removed.

- The temporality of when a catheter is removed or if it is removed is variable based on the individual patient’s needs as well as a physician’s clinical expertise.

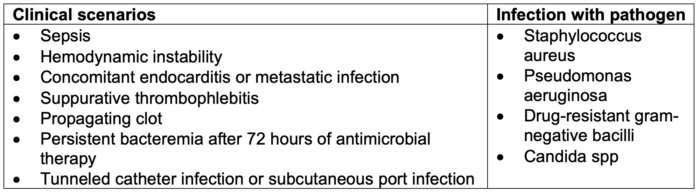

- Catheter salvage is typically done with the addition of antibiotic lock therapy; however, removal of the catheter in addition to systemic antimicrobial therapy is indicated in the following scenarios and infections with certain pathogens (Table 1).

Table 1. Indications for catheter removal in the setting of CRBSI. Adapted from Calderwood MS. Intravascular non-hemodialysis catheter-related infection: Treatment. UpToDate; 2024.

Treatment for Bacterial CRBSI5

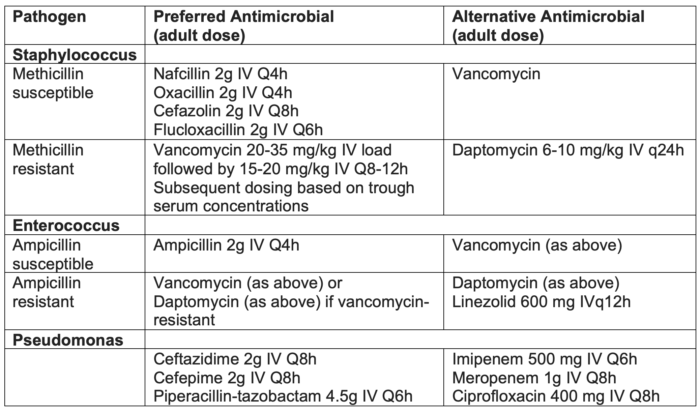

- All patients with suspected CRBSI should be started empirically on vancomycin.

- Patients with a known source of gram-negative or confirmed gram-negative on gram stain can be started empirically on cefepime in addition to vancomycin.

- Once the patient has blood cultures that identify the exact microorganism, antibiotic therapy can be narrowed to avoid extraneous antibiotic usage (Table 2).

Table 2. Antimicrobial treatment for CRBSI. Adapted from Calderwood MS. Intravascular non-hemodialysis catheter-related infection: Treatment. UpToDate; 2024.

Treatment for Fungal CRBSI5,6

- Most commonly caused by Candida species and the first line of treatment is echinocandins.

- Caspofungin 70 mg IV loading dose, followed by 50 mg IV daily

- Micafungin 100 mg IV daily

- Anidulafungin 200 mg IV loading dose, then 100 mg IV daily

- Patients who are not critically ill and do not have resistant Candida can receive fluconazole 800 mg (12 mg/kg) oral-loading dose, then 400 mg (6 mg/kg) orally daily.

Prevention

- Prevention of CRBSI is the best strategy for reducing bloodstream infections caused by catheters.

- Much of the data today points towards implementing a checklist so that there is a decreased chance of someone getting a CRBSI.

- The first step and arguably most important step is proper hand hygiene.2

- Using checklists that provide step-by-step instructions for inserting a catheter using proper infection control (wearing a mask, cap, sterile gown and gloves and placing a large sterile drape) have been shown to improve adherence to sterile technique.2

- Antisepsis with alcoholic chlorhexidine skin has become the standard of care and has been shown to be superior to povidone-iodine, secondary to its rapid onset of action, shorted drying time, persistent activity despite exposure to blood and bodily fluids, and a longer residual effect at the insertion site.2

- The subclavian site has the lowest risk of infection for patients in the intensive care unit. However, site selection is guided by patient comorbidities (coagulopathies, anatomy, and preexisting catheters), patient comfort, and the ability to secure the catheter.2

- Chlorhexidine dressings can reduce the risk of CRBSI and should be routinely used in patients who are older than two months of age. Providers can use gel-based formulas as well as chlorhexidine-impregnated sponges.

- Catheters impregnated with chlorhexidine silver sulfadiazine or minocycline rifampin have been studied for many years and continuously show superior results in reducing bloodstream infections.

- Lastly, catheter hubs and caps have long been recognized as a source of CRBSI. Another preventative measure is to “scrub the hub” with alcohol or chlorhexidine for 10 to 15 seconds and then allowing it to dry before accessing the catheter.2

References

- Cabrero LE, Robledo TR, Cuñado CA, et al. Risk factors of catheter- associated bloodstream infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Murt A, ed. PLOS ONE. 2023;18(3): e0282290. PubMed

- O’Grady NP. Prevention of central line–associated bloodstream infections. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(12):1121-31. PubMed

- Allon M, Sexton DJ. Tunneled hemodialysis catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI): Epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis. In: Post T (ed): UpToDate; 2024. Accessed January 27, 2024 Link

- Jacob JT. Intravascular catheter-related infection: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and microbiology In Post T (ed): UpToDate; 2024. Accessed January 28, 2024 Link

- Calderwood MS. Intravascular non-hemodialysis catheter-related infection: Treatment. In Post T (ed): UpToDate; 2024. Accessed January 28, 2024. Link

- Vazquez JA. Management in candidemia and invasive candidiasis in adults In Post T (ed): UpToDate; 2024. Accessed on March 14, 2024 Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.