Copy link

Perioperative Drug Safety

Last updated: 04/03/2024

Key Points

- Safety issues with anesthetics such as halogenated anesthetics hepatotoxicity, nitrous oxide(N2O)-related myeloneuropathy, and propofol-related infusion syndrome are getting more attention.

- Safety problems of new drugs are not always detected during clinical trials used for licensing purposes and may take many years to emerge.

- A good safety culture within the work area will include all professional groups and multiple aspects of practice, with medication administration being just one.

Introduction

- It is common for anesthesiologists to have complete responsibility for all steps of the medication handling process in the complex and fast-changing operating room environment, without the safety mechanisms of computer decision support or pharmacy input that are common in other settings.

- Medication errors in the operating room have been linked to:

- Mental calculations

- Distractions

- Task overload

- Time pressures

- Nonstandard medication processes

- Safety issues with anesthetics such as halogenated anesthetics hepatotoxicity, N2O-related myeloneuropathy, and propofol-related infusion syndrome are getting more attention.

- With the newer medications being used in the operating room, a careful and critical approach to the use of new drugs is needed to ensure their use is appropriate. In addition to allergies and anaphylaxis, physicians must be vigilant in detecting and reporting possible adverse reactions.

- To enhance drug safety, all professional groups and multiple aspects of practice should be included in the development of a good safety culture within the work area, including

medication administration.1

Current Anesthetics Safety Issues

- Halogenated anesthetics hepatotoxicity2

- Beginning with halothane in the 1950s, halogenated anesthetics replaced the routine use of ether and chloroform. However, postoperative liver injury was soon recognized, especially in patients re-exposed to halothane. Hepatitis followed by halothane anesthesia has high morbidity and mortality rates and surviving patients may require a liver transplantation.

- The next generation of halogenated anesthetics, including enflurane, isoflurane, desflurane, and sevoflurane have different molecular structures and are associated with less hepatotoxicity; however, rare instances of acute liver injury have been reported with all of these agents.

- The pattern of liver injury described with the newer halogenated anesthetics (enflurane, isoflurane and desflurane) has resembled that of halothane mechanism and evidence of autoimmune response to trifluoroacetylated liver proteins has been identified in patients’ serum.

- A history of anesthesia-induced hepatitis is a reason to avoid subsequent exposure to halothane or other halogenated anesthetics, since crossed immunity can rarely occur.

- Unlike other halogenated anesthetics, sevoflurane is not metabolized to hepatotoxic trifluoroacetylated proteins; however, very few reports have described liver injury after sevoflurane exposure.

- N2O-related myeloneuropathy3

- The characterization of the clinical presentation of myeloneuropathy induced by nitrous oxide has only been reported in small case series.

- N2O-myeloneuropathy results from functional vitamin B12 deficiency, which leads to a failure in the production of myelin, notably damaging the dorsal columns of the spinal cord through subacute combined degeneration (SACD), that is identifiable on MRI.

- Neuropathy on nerve conduction studies has also been described. Low pre-exposure B12 levels increase susceptibility to SACD, with shorter exposures to N2O.

- The mainstay of treatment currently available for N2O-myeloneuropathy is the cessation of use and parenteral vitamin B12 supplementation.

- Propofol-related infusion syndrome (PRIS)4

- PRIS is a lethal condition characterized by multiple organ system failures. It can occur due to prolonged administration of propofol in mechanically intubated patients.

- The main presenting features of this condition include cardiovascular dysfunction with particular emphasis on impairment of cardiovascular contractility, metabolic acidosis, lactic acidosis, rhabdomyolysis, hyperkalemia, lipidemia, hepatomegaly, acute renal failure, and eventually mortality in most cases.

- The significant risk factors that predispose patients to PRIS include critical illnesses, increased serum catecholamines, steroid therapy, obesity, young age (significantly, below three years), depleted carbohydrate stores in the body, increased serum lipids, and most importantly, large or extended dosage of propofol.

- The primary pathophysiology behind PRIS is the disruption of the mitochondrial respiratory chain that causes inhibition of adenosine triphosphate synthesis and cellular hypoxia.

Issues with Newer Medications

- The safety profile of new drugs often cannot be fully assessed as:

- There is insufficient quality published evidence to judge an effective new drug.

- They have not been tested as widely as other therapies.

- By the time of licensing, only a limited number of patients will have been exposed to the drug.

- Innovative physicians face a dilemma as they strive to provide their patients with the best available therapeutic intervention without exposing them to unknown risks. To ensure the appropriate use of new drugs, a careful and critical approach is required. Physicians must be vigilant to detect and report possible adverse effects.5

- Among the new drugs introduced to the United States between 1975 and 1999, 10% had serious adverse effects that emerged only after approval. According to U.S. postmarketing surveillance, serious adverse drug reactions were only identified a median of three years after approval from 1998 to 2004.

- The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is responsible for ensuring that novel therapeutics are safe and effective. From 1963 to 2004, 40% of safety withdrawals in Canada occurred within three years of registration.2 In making approval decisions, the FDA weighs the risks and benefits of novel therapeutics based on premarket drug testing and clinical trials.6

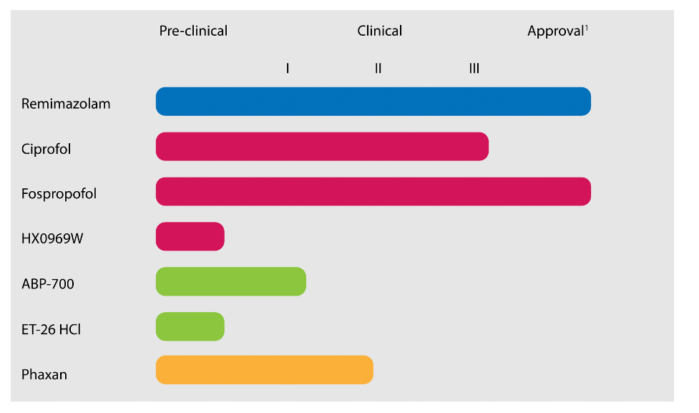

- New hypnotic agents7

- The anesthetic agent should have a rapid onset of action and an equally rapid, organ-independent clearance, so that its effect can be tightly controlled.

- It does not affect circulatory and respiratory systems in a negative way and has a minimal amount of side effects.

- It should also have additional desirable properties, such as antiemetic or analgesic effects.

Figure 1. Overview of novel hypnotics and their current status in drug development by the FDA. Blue: Benzodiazepine derivative. Red: Propofol derivatives. Green: Etomidate derivatives. Orange: Steroid. Source: Vellinga R, et al. What's new in intravenous Anaesthesia? New hypnotics, new models and new applications. J Clin Med. 2022;11(12):3493. PubMed. CC BY 4.0.

Best Practices for Medication Administration

- A good safety culture will encompass all professional groups and multiple aspects of practice, including medication administration. The culture includes:

- Staff should be encouraged to speak up if something seems amiss.

- Comments or questions from any member of the team should be taken as clarifications that may prevent errors rather than criticism.

- Work areas should be standardized as much as possible.1

- The FDA’s Sentinel Initiative, which combines administrative claims and clinical data, is an important first step since the integration of multiple data sources, including:

- Observations among large and diverse patient populations

- Facilitating the detection of postmarket safety events

- Boosting efforts to identify postmarket safety events more promptly

- Despite the most careful regulatory review and sensitive postmarket surveillance mechanisms, it may be impossible to detect other less common events until several years after approval, once the therapeutics have been widely used.6

Recommendations for Preventing Medication Errors

- In 2010, the Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation (APSF) published a paradigm for medication safety in the operating room that eliminates human factors as much as possible. It consists of four components.8

- Standardization of drugs, concentrations, and equipment: Drug units and concentrations should be standardized throughout the workplace to avoid confusion between preparations. Drug preparation methods should be standardized between personnel.

- Technology-assisted drug identification and delivery and automated information systems: Anesthetizing locations should be equipped with computerized mechanisms (e.g., barcode readers) to correctly identify and confirm the identity and details of medications within vials, ampules, and syringes.

- Pharmacy-based assistance with a specialized satellite pharmacy, solely for the operating room, that provides premixed solutions and prefilled syringes of anesthesia medications: Prefilled bolus medication syringes and solutions for infusions eliminate errors made by anesthesia providers while transferring and diluting drugs from vial to syringe, because this step no longer exists.

- Medication errors should be investigated using a “just culture” approach. Reporting of errors followed by a nonpunitive discussion to understand the root causes of these errors (and near misses) will reduce recurrences and contribute to the development of systematic processes to prevent their future occurrence.

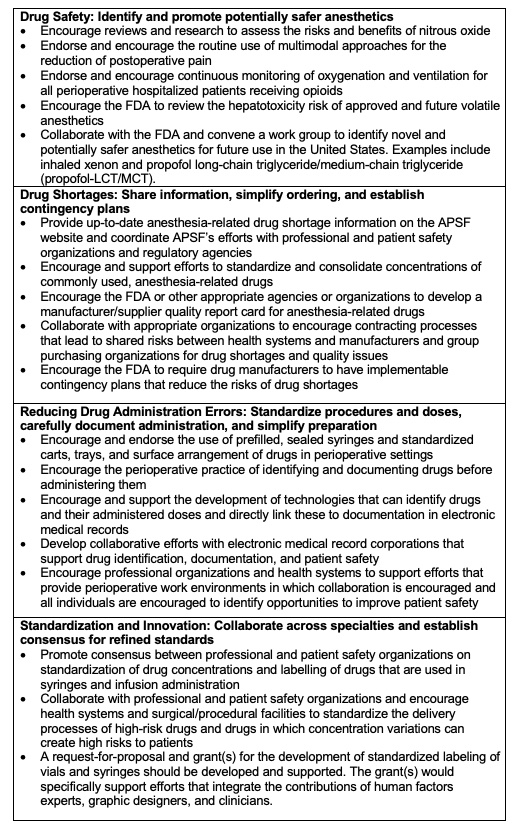

- The APSF’s Stoelting Conference on Medication Safety in 2018 recommended focusing on changes that address safety issues related to drugs and their administration. The specific recommendations of the conference are listed in Table 1.9

Table 1. APSF’s medication safety recommendations. Used with permission from the APSF

References

- Kinsella SM, Boaden B, El-Ghazali S, et al. Handling injectable medications in anaesthesia: Guidelines from the Association of Anaesthetists. Anaesthesia. 2023;78(10):1285-94. PubMed

- Safari S, Motavaf M, Seyed Siamdoust SA, et al. Hepatotoxicity of halogenated inhalational anesthetics. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(9):220153. PubMed

- Mair D, Paris A, Zaloum SA, et al. Nitrous oxide-induced myeloneuropathy: a case series. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2023;94(9):681-8. PubMed

- Singh A, Anjankar AP. Propofol-related infusion syndrome: A clinical review. Cureus. 2022;14(10);e30383. PubMed

- Pegler S, Underhill J. Evaluating the safety and effectiveness of new drugs. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(1):53-7. PubMed

- Downing NS, Shah ND, Aminawung JA, et al. Postmarket safety events among novel therapeutics approved by the US Food and Drug Administration between 2001 and 2010. JAMA. 2017;317(18):1854-63. PubMed

- Vellinga R, Valk BI, Absalom AR, et al. What's new in intravenous anaesthesia? New hypnotics, new models and new applications. J Clin Med. 2022;11(12):3493. PubMed

- Eicchorn JH. APSF hosts medication safety conference: consensus group defines challenges and opportunities for improved practice. APSF Newsletter 2019;1:1-20. Link

- Recommendations Of the four work groups at the 2018 APSF Stoelting conference on medication safety. Link

Other References

- APSF Video Library. Medication Safety In The Operating Room: Time For A New Paradigm Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.