Copy link

Neuraxial Opioids

Last updated: 06/29/2023

Key Points

- The bioavailability of neuraxial opioids is inversely proportional to the drug’s lipid solubility. Hydrophilic opioids such as morphine have a higher neuraxial bioavailability than lipophilic opioids such as fentanyl, sufentanil, or alfentanil.

- The density and duration of opioid concentration at the level of the spinal cord influences whether the drug acts via direct spinal mechanism or supraspinal effect.

- Patients who receive neuraxial opioids should have respiratory monitoring secondary to the risk of respiratory depression.

History

- Neuraxial opioids have been utilized in clinical practice for more than a century with an excellent safety profile. The use of neuraxial opioids was first reported in 1901 by a surgeon describing spinal analgesia with cocaine and morphine. The first use of epidural morphine was reported in 1979.1

- The popularity of neuraxial opioids rose in the mid 1970s when the endogenous opioid system was discovered as well as the evidence of the presence of opioid receptors in nerve tissue.

Mechanism of Action of Neuraxial Opioids

- Opioids bind to specific opioid receptors in the central nervous system, gastrointestinal tract, and other tissues. The major opioid receptors are mu (μ, with subtypes μ1, μ2, and μ3), kappa (κ), delta (δ), zeta (ζ), and nociception receptors.

- Opioids produce analgesia by a common molecular mechanism, via a decrease in the excitability of nerve cells. This occurs by:

- binding to the opioid receptors, which are coupled to G-protein;

- inhibition of the enzyme adenylate cyclase;

- activation of potassium channels; and

- inhibition of voltage-dependent calcium channels.

- Opioids administered in the neuraxial space provide analgesia is provided in two ways:

- Direct spinal mechanism: Once the drug has diffused into the intrathecal space

- Supraspinal effect: Occurs following systemic absorption

- Neuraxial opioids provide analgesia by acting on mu receptors in the substantia gelatinosa of the spinal cord.

- Opioids administered in the epidural space must diffuse across the dura to bind to mu receptors in the spinal cord.

- Opioids administered in the intrathecal space acts directly on the mu receptors in the spinal cord, thereby requiring a lower dose (5-10 times less than the epidural dose).

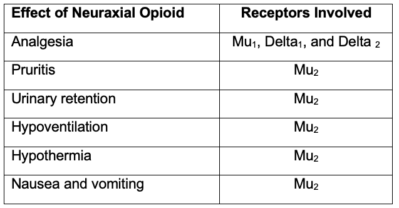

- The effects of neuraxial opioids and the receptors involved are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Effects of neuraxial opioids and the receptors involved

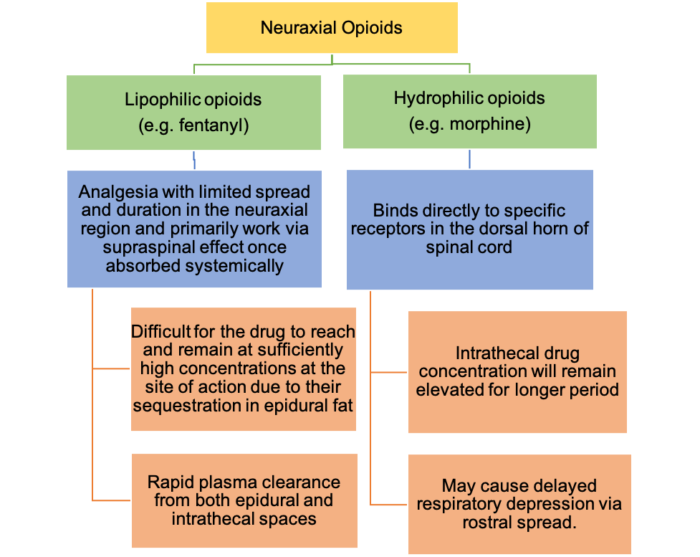

Bioavailability of Neuraxial Opioids

- The bioavailability of neuraxial opioids is inversely proportional to the drug’s lipid solubility. Hydrophilic opioids such as morphine have a higher neuraxial bioavailability than lipophilic opioids such as fentanyl, sufentanil, or afentanil.1

Figure 1. Bioavailability of neuraxial opioids

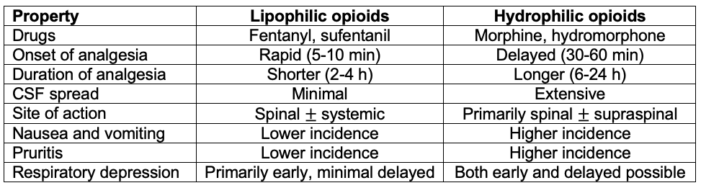

- The properties of neuraxial opioids are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Properties of neuraxial opioids. Adapted from Hurley RW, Elkassabany NM, Wu CL. Acute postoperative pain. In: Gropper MA (ed). Miller’s Anesthesia. Ninth edition. Philadelphia, PA. Elsevier; 2020: 2614-38.2

Equianalgesic Dosing of Neuraxial Opioids

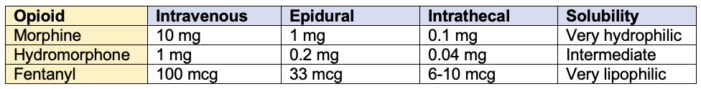

- Accurate ratios to convert between the various routes of opioid administration (intravenous, epidural, and intrathecal) are still uncertain.3

- Historically, a ratio of 100 IV:10 epidural:1 intrathecal has been commonly accepted when converting opioids between these routes of administration.

- Parenteral to neuraxial dose conversions are more complex and less reliable since each route differs pharmacokinetically as well as mechanistically, meaning opioids work quite differently when administered neuraxially.

- Calculating the conversion of opioids between various routes of administration (epidural, intrathecal and intravenous) is based on consensus and expert opinion rather than strong evidence. Table 3 summarizes recommendations based on a literature review of the topic, although final doses should be based on patient factors, such as opioid tolerance, age, and co-morbidities.4

Table 3. Equianalgesic dosing of intravenous and neuraxial opioids. Final doses should be based on patient factors, such as opioid tolerance, age, and comorbidities.3

Respiratory Depression Following Neuraxial Opioids

- The American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on neuraxial opioids published practice guidelines for the prevention, detection, and management of respiratory depression associated with neuraxial opioid administration.5 The summary of the recommendations are as follows:

Identification of Patients at Increased Risk5

- A focused history and physical examination should be performed before administering neuraxial opioids.

- Attention should be directed to a history, signs, and symptoms of sleep apnea and/or coexisting diseases such as diabetes or obesity.

- Current medications for possible adverse effects after opioid administration should be reviewed.

- Physical examination should include vital signs, and an evaluation of the airway, heart, lungs, and cognitive function.

Prevention of Respiratory Depression5

- Patients with a history of sleep apnea treated with noninvasive positive airway pressure should be encouraged to bring their own equipment to the hospital.

Drug Selection5

- Single injection neuraxial opioids can be safely used instead of parenteral opioids without increasing the risk of respiratory depression or hypoxemia.

- Single injection neuraxial fentanyl or sufentanil may be safe alternatives to single injection neuraxial morphine.

- When clinically suitable, appropriate doses of continuous epidural infusion of fentanyl or sufentanil may be used in place of continuous infusion of morphine or hydromorphone without increasing the risk of respiratory depression.

- Given the unique pharmacokinetic effect of the various neuraxially administered opioids, appropriate duration of monitoring should be matched with the drug.

- Based on the duration of action of hydrophilic opioids, neuraxial morphine or hydromorphone should not be administered to outpatient surgical patients.

Dose Selection (Low Dose versus High Dose Neuraxial Opioids)

- The lowest efficacious dose of neuraxial opioids should be administered to minimize the risk of respiratory depression.

Drug Combinations5

- Parenteral opioids or hypnotics (e.g., ketamine) should be administered cautiously in the presence of neuraxial opioids and the concomitant administration of neuraxial opioids and parenteral opioids, sedatives, hypnotics, or magnesium requires increased monitoring (e.g., intensity, duration, or additional monitoring).

Monitoring for Respiratory Depression5

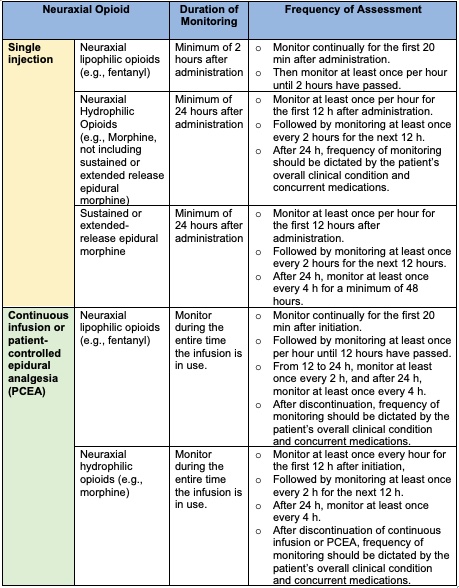

- Monitoring is dependent on the drug selected for neuraxial administration (Table 4).

Table 4. Monitoring for respiratory depression with the use of neuraxial opioids.

Management and Treatment of Respiratory Depression5

- For patients receiving neuraxial opioids, supplemental oxygen should be available.

- Supplemental oxygen should be administered to patients with altered level of consciousness, respiratory depression, or hypoxemia and continued until the patient is alert and no respiratory depression or hypoxemia is present.

- Intravenous access should be maintained if recurring respiratory depression occurs.

- Reversal agents should be available for administration to all patients experiencing significant respiratory depression after neuraxial opioid administration.

- In the presence of severe respiratory depression, appropriate resuscitation should be initiated.

- Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation may be considered for improving ventilatory status.

- If frequent or severe airway obstruction or hypoxemia occurs during postoperative monitoring, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation should be initiated.

References

- Bujedo BM. Spinal opioid bioavailability in postoperative pain. Pain Pract. 2014; 14(4), 350–364. PubMed

- Hurley RW, Elkassabany NM, Wu CL. Acute postoperative pain. In: Gropper MA (ed). Miller’s Anesthesia. Ninth edition. Philadelphia, PA. Elsevier; 2020: 2614-38.

- Gorlin AW, Rosenfeld DM, Maloney J, et al. Survey of pain specialists regarding conversion of high-dose intravenous to neuraxial opioids. J Pain Res. 2016;9: 693-700. PubMed

- Kim DD, Patel A, Sibai N. Conversion of intrathecal opioids to fentanyl in chronic pain patients with implantable pain pumps: A retrospective study. Neuromodulation. 2019; 22(7): 823-27. PubMed

- An Updated Report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Neuraxial Opioids. (2009). Practice guidelines for the prevention, detection, and management of respiratory depression associated with neuraxial opioid administration. Anesthesiology. 2009;110(2): 218-30. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.