Copy link

Neuropathic Pain: Etiology, Pathophysiology, and Diagnosis

Last updated: 02/13/2024

Key Points

- Neuropathic pain is a clinical description (not a diagnosis) of pain caused by a lesion or disease of the central or peripheral somatosensory nervous system.

- Multiple causes of neuropathic pain, both peripheral and central in origin, have been described.

- The complex pathophysiology of neuropathic pain involves changes in peripheral nociceptive fibers, increased neuronal hyperexcitability, ectopic activity, altered signal transmission, central sensitization, and imbalances between excitatory and inhibitory signals.

Definition

- According to the International Association for the Study of Pain, neuropathic pain is a clinical description (not a diagnosis) of pain caused by a lesion or disease of the central or peripheral somatosensory nervous system.1

- The somatosensory systems includes mechanoreceptors, thermoreceptors, chemoreceptors, pruriceptors, and nociceptors that send signals to the spinal cord and brain and allow for the perception of pain, touch, pressure, temperature, position, movement, and vibration.2

- Lesions or diseases of the somatosensory nervous system result in altered and disordered transmission of sensory signals to the spinal cord and brain. Common conditions associated with neuropathic pain include postherpetic neuralgia, trigeminal neuralgia, diabetic neuropathy, painful radiculopathy, human immunodeficiency virus infection, leprosy, amputation, central poststroke pain, etc.2

- Patients experience symptoms such as burning and electrical-like sensations, and pain from nonnoxious stimuli, such as light touch. Sleep deprivation, anxiety, and depression are common, resulting in impaired quality of life.

- Unique characteristics of neuropathic pain include spontaneous pain, hyperalgesia, and allodynia.

- Spontaneous pain is defined as pain that occurs with no identifiable stimulus.

- Hyperalgesia is increased pain from a stimulus that normally provokes pain.

- Allodynia is pain due to a stimulus that does not normally provoke pain.1 Initially, the term nonnoxious stimulus was used to describe allodynia, but it was subsequently removed.

- It should be noted that with allodynia, the stimulus and the response are in different modes, whereas with hyperalgesia, they are in the same mode.1

Epidemiology

- The exact prevalence of neuropathic pain has been difficult to quantify secondary to the lack of uniform diagnostic criteria. Based on recent screening tools, such as the Douleur Neuropathique 4 questions and the Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs, the estimated prevalence of neuropathic pain is approximately 7-10%.2

- Chronic neuropathic pain is more common in women (8% vs. 5.7% in men) and in patients older than 50 years (8.9% vs. 5.6% in patients younger than 50 years).2

- Neuropathic pain most commonly affects the lower back and lower limbs, neck, and upper limbs.2

Classification of Neuropathic Pain

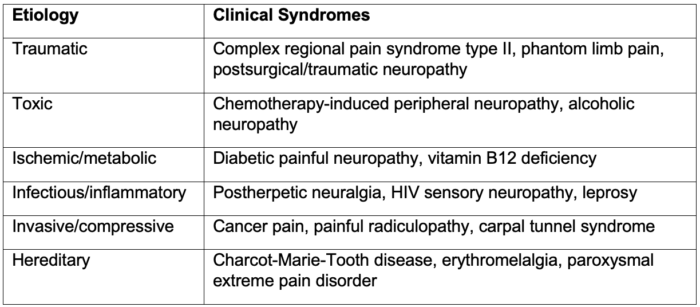

- Neuropathic pain can be divided into two categories: consequences of a central lesion vs. peripheral lesion (Table 1).2,3

- Central neuropathic pain is caused by lesions or diseases of the spinal cord and/or brain.2

- Spinal cord lesions causing neuropathic pain include spinal cord injury, syringomyelia, and demyelinating diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, transverse myelitis, etc.

- Brain lesions causing neuropathic pain include poststroke pain, Parkinson disease, etc.

- Peripheral neuropathic pain on the other hand involves the small unmyelinated C fibers and the myelinated Aβ and Aδ fibers.

- Peripheral neuropathic pain can be subdivided into those that have a generalized (usually symmetrical) distribution versus a focal distribution.2

- Generalized distribution: diabetic neuropathy, infectious diseases (HIV, leprosy), chemotherapy, Guillain-Barre syndrome, inherited neuropathies, channelopathies, etc. The topography of pain is typically a “glove and stocking” distribution.

- Focal distribution: postherpetic neuralgia, trigeminal neuralgia, posttraumatic neuropathy, cervical and lumbar polyradiculopathies, etc.

- Peripheral neuropathic pain can also be subdivided into categories based on the etiology (Table 1).3

Table 1. Common clinical syndromes causing peripheral neuropathic pain

Pathophysiology

Peripheral Mechanisms in Neuropathic Pain

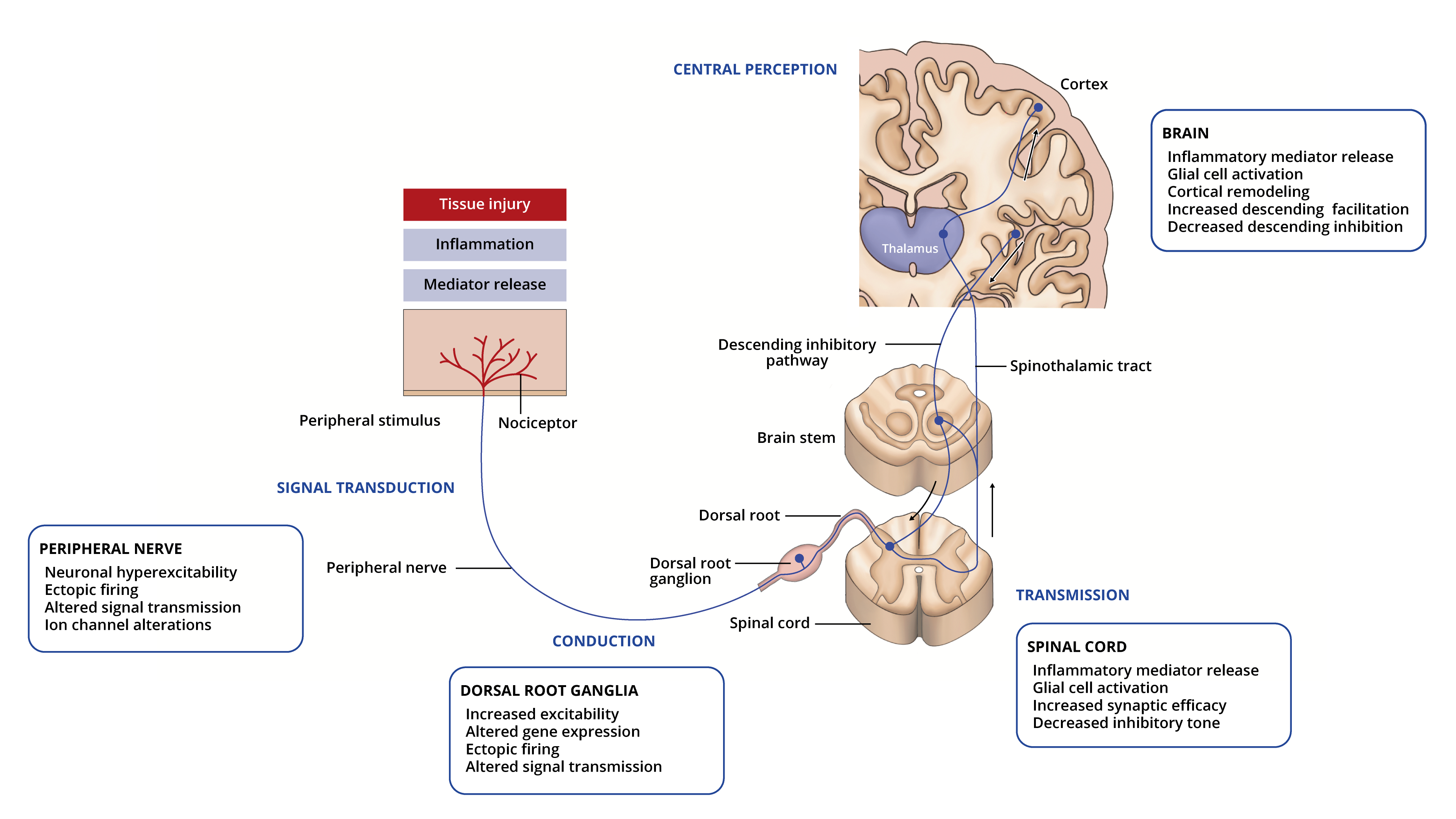

- An initial insult or injury causes damage to the primary afferent fibers (unmyelinated C fibers and myelinated Aβ and Aδ fibers) and results in changes in peripheral nociceptive fibers, increased neuronal hyperexcitability, ectopic activity, and altered signal transmission from ion channel alterations, such as increased expression of excitatory sodium and calcium channels, and downregulation of attenuating potassium channels (Figure 1).

- Similarly, injuries along the axons and dorsal root ganglia induce fiber degeneration and alterations in channel expression and composition, ectopic firing, and faulty signal transmission.

Central Mechanisms in Neuropathic Pain

- With repeated or sufficiently intense stimulation, spinal and supraspinal nociceptive pathways become sensitized to subsequent stimuli, resulting in central sensitization.3

- The increased responsiveness of second-order neurons can involve changes in calcium permeability, receptor overexpression, and synapse location.

- In supraspinal regions, there is an imbalance between the descending inhibitory pathways and excitatory pathways and the brain receives altered and abnormal sensory messages.2

- Altered projections to the thalamus and cortex account for the high pain ratings and anxiety, depression, and sleep problems.3

Figure 1. Peripheral and central mechanisms in neuropathic pain. Pain pathway adapted from Pain: types and pathways. Lecturio.com.

Diagnosis

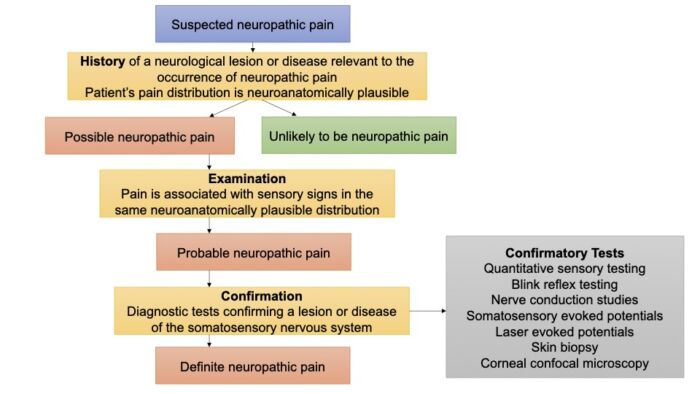

- A proposed algorithm for diagnosing neuropathic pain is shown in Figure 2.4

Figure 2. Algorithm for diagnosing neuropathic pain. Adapted from Finnerup NB, et al. Neuropathic pain: an updated grading system for research and clinical practice. Pain. 2016; 157(8): 1599-1606. PubMed

History4

- There should be a clinical suspicion of a relevant lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system (e.g., an episode of a traumatic nerve injury, herpes zoster, etc.).

- The onset of pain is usually immediate or within a few weeks of the injury but may be delayed for several months or years. A close temporal relationship helps strengthen the clinical suspicion.

Pain Distribution is Neuroanatomically Plausible4

- The pain distribution should be anatomically plausible with the suspected lesion or disease.

- Trigeminal neuralgia: face or intraoral trigeminal territory

- Postherpetic neuralgia: unilateral distribution in one or more spinal dermatomes

- Peripheral nerve injury pain: in the innervation territory of the lesion nerve

- Postamputation pain: in the missing body part and/or in the residual limb

- Painful polyneuropathy: in the feet (may extend to lower legs and thighs) and hands

- Painful radiculopathy: in the distribution of the nerve root

- Spinal cord injury: at and/or below the level of the spinal cord lesion

- Central poststroke pain: contralateral to the stroke

Physical Examination4

- The physical exam should confirm the presence of negative sensory signs, i.e., partial, or complete loss to one or several sensory modalities (e.g., light touch, cold temperature, vibration, pinprick, pressure) and distinct delineation of the area affected by the negative sensory phenomena that is concordant with the lesion or disease of the somatosensory system.

- There are certain conditions such as hereditary channelopathies where sensory loss may not be present.

- Positive sensory signs alone (e.g., pressure-evoked hyperalgesia) especially if their distribution doesn’t follow neuroanatomical delineation, carry less weight in diagnosing neuropathic pain.

Confirmatory Tests2

- Typically, these confirmatory tests are performed in the sequence of increasing invasiveness as listed below.

- Quantitative sensory tests use standardized mechanical and thermal stimuli to test the different afferent fibers (Aβ, Aδ, and C fibers).

- In the blink reflex test, the trigeminal afferent system is investigated by recording responses from the orbicularis oculi muscles.

- Nerve conduction studies assess nonnociceptive fiber function of the peripheral nerves.

- Somatosensory evoked potentials and laser evoked potentials, both recorded from the scalp, investigate large and small afferent fiber function. Laser-evoked potentials related to Aδ fiber activation are considered the most reliable neurophysiological tool to assess nociceptive functions.

- A skin biopsy quantifies the intraepidermal nerve fibers, which provides a measure of small-fiber loss. It is the most sensitive tool for diagnosing small-fiber neuropathies.

- Corneal confocal microscopy assesses corneal innervation and quantifies corneal nerve fiber damage.

Screening Tools2

- Several screening tools have been developed to diagnose neuropathic pain. Some examples are listed below.

Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs

- Four symptoms (prickling, tingling, pins and needles; electric shocks; hot or burning sensations; and pain evoked by light touch

- One item related to skin appearance (mottled or red)

- Two clinical exam items (touch-evoked allodynia and altered pinprick sensations)

Douleur Neuropathique 4 questions

- Seven symptoms (burning, painful cold, electric shocks, tingling, pins and needles, numbness, and itching)

- Three clinical exam items (touch hypoesthesia, pinprick hypoesthesia, and brush-evoked allodynia)

Neuropathic Pain Questionnaire

- Seven sensory descriptors (burning pain, shooting pain, numbness, electrical-like sensations, tingling pain, squeezing pain, and freezing pain)

- Three items related to provoking factors (overly sensitive to touch, touch-evoked pain, and increased pain during weather change)

- Two items describing affect (unpleasantness and overwhelming)

painDETECT

- Seven weighted symptoms (burning, tingling or prickling, touch-evoked pain, electric shocks, temperature-evoked pain, numbness, and pressure-evoked pain

- Two items related to spatial (radiating pain) and temporal characteristics

References

- Merskey H, Bogduk N. International Association for the Study of Pain Terminology Working Group. Definition of pain. IASP. Publish date 1994. Updated 2022. Accessed December 28th, 2023. Link

- Colloca L, Ludman T, Bouhassira D, et al. Neuropathic pain. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017; 3:17002. PubMed

- Meachem K, Shepherd A, Mohapatra DP, et al. Neuropathic pain: central vs. peripheral mechanisms. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2017; 21(6): 28. PubMed

- Finnerup NB, Haroutounian S, Kamerman P, et al. Neuropathic pain: an updated grading system for research and clinical practice. Pain. 2016; 157(8): 1599-1606. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.