Copy link

Patient-Controlled Analgesia

Last updated: 04/04/2023

Key Points

- Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) is an electronically controlled infusion pump that delivers a programmed amount of analgesia with a bolus dose with or without a basal infusion.

- The safety and benefits of PCA have been extensively proven in the literature, dating back to the 1970s.

- Given the potential for opioid-related side effects, continuous monitoring to detect respiratory depression and oversedation is highly recommended in order to alert nursing staff to initiate interventions.

- Nurse/caregiver-controlled analgesia is an option for patients who are too young or not developmentally appropriate to make such decisions.

Definitions

- PCA refers to an electronically controlled infusion pump that delivers a specific amount of intravenous analgesic through tubing connected to an intravenous line when the patient presses a button. First used in adults in 1965 and has been used in the pediatric population since the late 1980s.

Benefits1,2

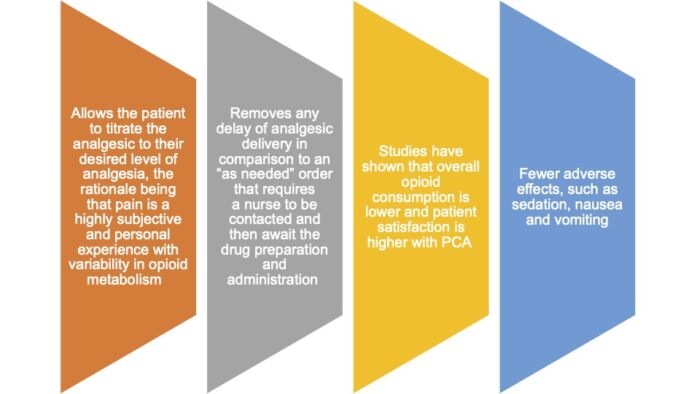

There are several benefits of PCA over conventional dosing of opioids (Figure 2). In a 2015 Cochrane review of 49 randomized trials comparing PCA to other methods for postoperative analgesia, PCA improved patient satisfaction and reduced pain scores.1 In terms of safety, studies have demonstrated a favorable safety profile, including in the pediatric population.2

Figure 2. Benefits of PCA over conventional methods.

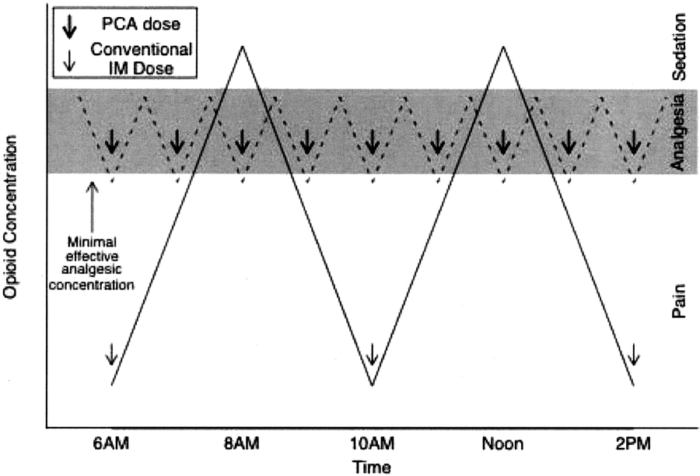

Figure 3. Graph representing difference in analgesic concentrations with two different regimens: intermittent bolus administration (nurse-administered analgesia) or frequent small doses (patient-controlled analgesia, PCA). Shaded area represents the target analgesic concentration. With intermittent bolus administration, there are frequent periods with concentrations more than and less than the target range. In contrast, PCA results in the opioid concentration being in the target range for a large percentage of the time. Used with permission from Grass JA. Patient-controlled analgesia. Anesth Analg. 2005;101 (5 Suppl): S44-61.3

Safety Precautions

- Patient selection for PCA is critical in the pediatric population and requires the child to understand when to utilize the PCA; thus, selection should be made on a case-by-case basis.

- Caregivers should never activate the pump as this may lead to oversedation and respiratory depression (unless the PCA has been designated as a nurse or caregiver-controlled analgesia).

- PCAs can be programmed to have a basal opioid infusion that runs continuously in the background in addition to a “button” that allows the patient to deliver a small bolus dose of an opioid.

- Basal infusions can aid in providing optimal analgesia, but they do carry increased risk:

- Basal infusions increase risk of respiratory depression, since opioid will infuse continuously even if patient is already sedated or sleeping.

- Studies show that PCA with basal infusions are correlated with higher incidents of respiratory depression.

- They should be used with caution in opioid naïve patients.

- A simple rule is that the continuous infusion should supply no more than 50% of total opioid requirement.3

- Opioid-related side effects such as nausea, vomiting, pruritis are exacerbated with a PCA basal infusion.

- For safety reasons, every PCA has:

- a key-enabled lock to only allow authorized persons to program the pump;

- a 4-hour lockout that sets a limit on the amount of opioid that can be delivered; and

- a lockout interval that sets a limit on how often a bolus dose can be delivered by the patient (usually between 5 to 15 minutes) and prevents additional dose from being delivered until full effect from the previous bolus is achieved.

- Although there are no standardized recommendations for monitoring when a patient has a PCA, the Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation (APSF) recommends the following during PCA.4

- Continuous respiratory monitoring (minimally pulse oximetry and a continuous measure of respiratory rate) should be present.

- Reliable alerting methods, such as audible alarms, central stations, or pagers, should be implemented to ensure timely and appropriate clinician response to the deteriorating respiratory status of patients receiving opioid therapy.

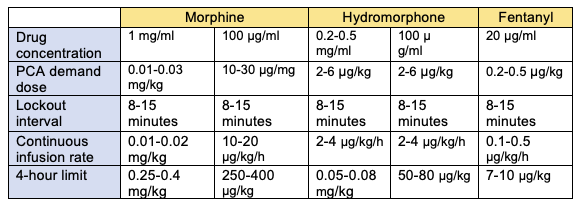

Table 1. PCA dosing for pediatric patients.2

Nurse/Caregiver Controlled Analgesia (NCA)5, 6

- In patients who are too young or not developmentally appropriate to operate a PCA, an NCA is a viable option.

- This modality allows a nurse or caregiver (nonhealthcare professional) to deliver a bolus dose via a button press.

- Studies have shown that children who received an NCA versus a PCA required more aggressive interventions to treat opioid-related side effects, such as opioid reversal, airway management, or escalation of care.

- Nevertheless, NCA is shown to be a safe delivery system, with one study of 10,000 pediatric patients confirming its safety profile.6

References

- McNicol ED, Ferguson MC, Hudcova J. Patient controlled opioid analgesia versus non-patient controlled opioid analgesia for postoperative pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015; CD003348. PubMed

- Walker BJ, Polaner DM, Berde CB. Acute Pain. In: Coté CJ, Lerman J, Anderson BJ. Coté and Lerman’s a practice of anesthesia for infants and children (6th edition). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018: 1023-62.

- Grass JA. Patient-controlled analgesia. Anesth Analg. 2005;101 (5 Suppl): S44-61. PubMed

- Weinger MB. Dangers of postoperative opioids: APSF workshop and white paper addresses prevention of postoperative complications. APSF Newsletter. 2006; 21:61. Link

- Monitto CL, Greenberg RS, Kost-Byerly S, et al. The safety and efficacy of parent-/nurse-controlled analgesia in patients less than six years of age. Anesth Analg. 2000;91(3):573-9. PubMed

- Howard RF, Lloyd-Thomas A, Thomas M, et al. Nurse-controlled analgesia (NCA) following major surgery in 10,000 patients in a children's hospital. Paediatr Anaesth. 2010;20(2):126-134. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.