Copy link

Sedation for the Pediatric Patient

Last updated: 04/06/2023

Key Points

- Sedation occurs on a continuum which includes minimal, moderate, and deep sedation before reaching general anesthesia.

- The pediatric patient may require deeper levels of sedation simply for behavioral or movement control.

- Presedation evaluations and periprocedural monitoring are critical components of responsible and safe patient care.

- A variety of pharmacologic options exist, and medication selection should be tailored to the patient’s condition/needs and the indication for sedation.

Introduction

- As the demand for minor procedures and diagnostic testing outside of the operating room increases, the administration of adequate sedation (anxiolysis and analgesia) is becoming increasingly important.

- Appropriate sedation for pediatric patients must incorporate special considerations related to the patient’s age, size, maturity, and cognitive ability.

- The pediatric patient may require sedation not only to prevent pain and anxiety, but also to manage behavior or limit movement to allow a procedure to be completed safely.

Depth of Sedation

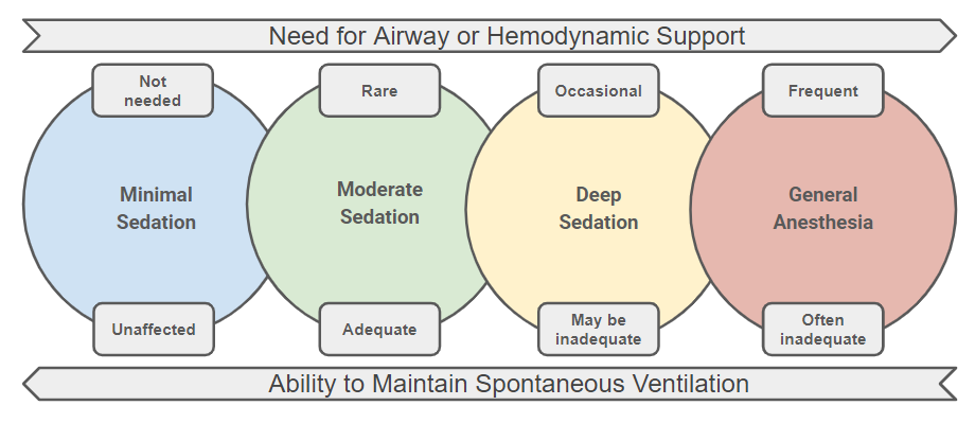

- Sedation occurs on a continuum with varying needs of anticipated airway and hemodynamic support.

- Minimal Sedation (“Anxiolysis”): May cause cognitive or physical impairment, but a normal response to verbal stimulation is maintained.

- Moderate Sedation (“Conscious Sedation”): State of depressed consciousness while maintaining a purposeful response to verbal or tactile stimulation.

- Deep Sedation: Patient is not easily aroused and has a purposeful response only to repeated or painful stimulation.

- General Anesthesia: Loss of consciousness; no purposeful response to painful stimulation.

Figure 1. Continuum of the depth of sedation

- Any practitioner performing sedation should be able to rescue (provide airway management and advanced life-support) a patient who reaches sedation of at least one level deeper than intended.

Monitored Anesthesia Care (MAC)

- While moderate sedation can be performed at the direction of a proceduralist, MAC is “a specific anesthesia service performed by a qualified anesthesia provider for a diagnostic or therapeutic procedure.”2

- MAC does not denote a specific level of sedation on the depth of sedation continuum.

- It may include “the need for deeper levels of analgesia and sedation than can be provided by moderate sedation (including potential conversion to a general or regional anesthetic).”2

Preprocedural Evaluation

- Presedation evaluation should mirror the evaluation of a patient undergoing general anesthesia.

Evaluation should include:

- Pertinent past medical history: problems with previous anesthetics, history of difficult airway, comorbidities (cardiac or pulmonary disease, obstructive sleep apnea, etc.), medications, and allergies.

- Focused physical examination: vital signs, airway evaluation, heart, and lung auscultation.

- Review of relative laboratory values or other diagnostic test results.

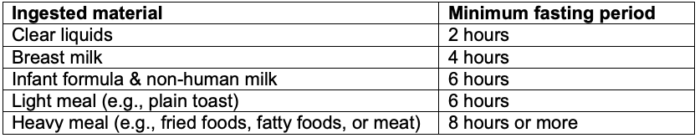

- Nil-per-os (NPO) status should be consistent with operating room guidelines.

Table 1. Fasting recommendations3

- A pediatric anesthesiologist should be consulted prior to the sedation of patients at an elevated risk of adverse events (e.g., ASA class III or IV, concerning airway evaluation, current respiratory infection, or any medical, mental, or psychological disabilities)

Monitoring

Ventilation and Oxygenation

- For moderate or deep sedation, continuous monitoring of the following should occur – oxygen saturation, respiratory rate, and capnography.

- Capnography is especially important in situations where direct visualization of the patient is impeded (e.g., MRI or under procedural drapes).

Hemodynamic Monitoring

- For moderate or deep sedation, continuous monitoring of the following should occur – heart rate, electrocardiography, and blood pressure (at 5-minute intervals).

Level of Consciousness

- The patient’s ability to respond to verbal, tactile, or painful stimulation should be assessed periodically (e.g., at 5-minute intervals).

- For pediatric patients where behavioral management or limiting movement are primary considerations, it may be prudent to assume the patient is a level deeper than the target depth of anesthesia to minimize disturbances.

Pediatric Sedation Scales

- Several scoring systems exist to monitor levels of sedation, though each uses stimulation to assess patient responsiveness and to quantitatively place a patient on the depth of sedation continuum.

- Commonly used sedation scales include:

- Ramsay Sedation Scale4 and Modified Ramsay Sedation Scale5

- University of Michigan Sedation Scale (UMSS)6

- Observer’s Assessment of Alertness/Sedation (OAA/S)7

Nonstimulating Consciousness Assessment

- Processed EEG monitoring, or the bispectral index (BIS) monitor, has been correlated to sedation scales with varying success.8

- BIS monitoring has many limitations in children including the inability to provide age-specific values, varying reliability with specific drugs, and marked overlap when trying to distinguish between levels of sedation.

Pharmacology

- The selection of medications should be targeted to accommodate the indication for sedation (i.e., analgesics for a painful procedure; sedative/hypnotics for a nonpainful procedure).

- A vast array of medications, combinations of therapies, and routes of administration exist. An extremely truncated list of pharmacologic agents is included below.

Analgesics

- Opioids (i.e., fentanyl, remifentanil): potent respiratory depressants. Ventilation must be carefully monitored.

- Ketamine: N-methyl D-aspartate receptor antagonist that produces dissociative sedation and analgesia. Preserves respiratory and cardiovascular function (may cause tachycardia and hypertension). Postprocedural nausea and vomiting is common. Antisialagogues can help reduce secretions. It is often coadministered with a benzodiazepine (midazolam) to reduce recall of dissociative symptoms and is available for oral, intramuscular, and intravenous (IV) use.

Sedative/Hypnotics

- Chloral hydrate: Oral sedative used in infants and children younger than 3 years for nonpainful procedures. Typical duration of action is 1-2 hours, but active metabolites have a half-life of up to 40 hours.8 It can cause respiratory depression, gastrointestinal effects, and prolonged agitation, so extended observation may be required.

- Propofol: The most commonly used sedative in pediatric anesthesia practice. It has short recovery times but can lead to respiratory and cardiovascular depression with no analgesia.

- Dexmedetomidine: α2-adrenergic receptor agonist used for procedural sedation. It has limited to no effect on respiration but be aware of its potential to cause mild hypotension and bradycardia. Consider using in combination with ketamine to supplement analgesia and to offset the negative hemodynamic effects. Can have a prolonged recovery period.

Anxiolytics/Amnestics

- Benzodiazepines (i.e., midazolam, diazepam, remimazolam): They are anxiolytic/amnestic that can improve patient compliance without loss of consciousness. They cause limited respiratory depression unless combined with opioids (“super additive effect”). There is no analgesic effect. They are available for oral, intranasal, and IV use.

Adverse Effects

- A multicenter, prospective review of more than 30,000 sedation encounters from the Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium reported the following adverse events.9

- Serious adverse events are rare, though some form of complication occurs in ~5% of pediatric sedations for procedures.

- One occurrence of cardiopulmonary resuscitation and zero deaths occurred.

- Vomiting occurred once in every 200 procedures.

- Stridor, laryngospasm, wheezing, or apnea occurred once in every 400 procedures.

- Unanticipated airway and ventilation interventions were required once in every 200 procedures.

- These results highlight the importance of emergency preparedness and presence of personnel able to provide airway management and advanced life-support.

Emergency Preparedness

- Age- and size-appropriate equipment for airway management and advanced life support must be readily available in all sedation locations, including the availability of emergency checklists.10

- For nonhospital-based sedation, a plan for contacting emergency medical services for life-threatening complications must be in place.

Personnel and Training

- While sedation may be performed by nonanesthesiologist practitioners, a pediatric anesthesiologist should be involved in the oversight, credentialing, and training of these individuals.11-13

- Institutional accreditation for pediatric sedation, obtained through the Society for Pediatric Sedation Center of Excellence, is highly encouraged.

References

- American Society of Anesthesiologists. Continuum of depth of sedation: Definition of general anesthesia and levels of sedation/ analgesia. Approved by ASA House of Delegates on October 13, 1999, and last amended on October 23, 2019. Link

- American Society of Anesthesiologists. Position on monitored anesthesia care. Approved by ASA House of Delegates on October 25, 2005, and last amended on October 17, 2018. PubMed

- Practice guidelines for preoperative fasting and the use of pharmacologic agents to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration: Application to healthy patients undergoing elective procedures: An updated report. Anesthesiology. 2017; 126:376–93. PubMed

- Ramsay MA, Savege TM, Simpson BR, Goodwin R. Controlled sedation with alphaxalone-alphadolone. Br Med J. 1974; 2:656-659. PubMed

- Agrawal D, Feldman HA, Krauss B, et al. Bispectral index monitoring quantifies depth of sedation during emergency department procedural sedation and analgesia in children. Ann Emerg Med. 2004; 43:247-255. PubMed

- Chernik DA, Gillings D, Laine H, et al. Validity and reliability of the Observer’s Assessment of Alertness/Sedation Scale: study with intravenous midazolam. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1990; 10:244-251. PubMed

- Malviya S, Voepel-Lewis T, Tait AR, et al. Depth of sedation in children undergoing computed tomography: validity and reliability of the University of Michigan Sedation Scale (UMSS). Br J Anaesth. 2002; 88:241-245. PubMed

- Kaplan RF, Cravero JP, Yaster M, et al. Sedation for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures outside the operating room. In: A Practice of Anesthesia for Infants and Children. Editors Cote CJ, Lerman J, Anderson BJ, Elsevier, 5th edition, Philadelphia, PA, 2019: 993-1013.

- Cravero JP, Blike GT, Beach M, et al. Incidence and nature of adverse events during pediatric sedation/anesthesia for procedures outside the operating room: Report from the Pediatric Sedation Research Consortium. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):1087-96. PubMed

- Cote CJ, Wilson, S, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guidelines for monitoring and management of pediatric patients before, during, and after sedation for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Pediatrics. 2019;143(6): e20191000. PubMed

- American Society of Anesthesiologists. Statement of granting privileges for administration of moderate sedation to practitioners. Approved by ASA House of Delegates on October 18, 2006, and last amended on October 13, 2021. PubMed

- Society for Pediatric Sedation. Pediatric Sedation Service Center of Excellence Consensus Statement. Published online Jan 19, 2016. PubMed

- Tobias JD. Sedation of infants and children outside of the operating room. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2015;28(4):478-85. PubMed

Other References

- Society for Pediatric Sedation. Sedation Resource Library. Accessed April 6, 2023. Link

- Society for Pediatric Sedation. Sedation Notes. Accessed April 6, 2023. Link

- Society for Pediatric Sedation. Infographics and Podcasts. Accessed April 6, 2023. Link

- Society for Pediatric Sedation. Pediatric Sedation Pocket Card for Providers. Accessed April 6, 2023. Link

- Society for Pediatric Sedation. SPS News. Accessed April 6, 2023. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.