Copy link

Stages of Anesthesia

Last updated: 12/21/2023

Key Points

- The stages of anesthesia describe a systematic approach to clinical assessment of anesthetic depth and readiness for stimulation, including surgery and airway manipulation.

- Signs of insufficient depth of anesthesia for surgical incision include an irregular breathing pattern, tachypnea, hypertension, divergent pupils, and breath-holding after laryngeal stimulation.

- Extubation should only be performed in an awake patient or when a patient is sufficiently anesthetized to blunt airway reflexes (Stage 3). During Stage 2 of anesthesia, patients are at higher risk for airway reactivity in response to airway stimulation.

Background

- Prior to the development of anesthetic monitors, physical examination offered the only means of assessing a patient’s anesthetic depth.1

- Providers with limited experience or poor clinical assessment could easily make a patient too light for surgical incision, leading to poor operating conditions or make a patient too deep, resulting in anesthetic overdose and poor patient outcomes.1

- Underscoring the importance and skill required to determine a patient’s anesthetic depth, John Snow, one of the early pioneers of ether anesthesia once wrote, “The point requiring most skill and care in the administration of the vapour ether is, undoubtedly, to determine when it has been carried far enough.”2

- In 1847, Snow proposed a system of classification of the depth of anesthesia that involved 5-stages of so-called “etherization.”3

- Several decades later, Dr. Arthur Guedel expanded upon Snow’s work to develop his own systematic approach to determining a patient’s anesthetic depth.3

Guedel’s Stages of Anesthesia

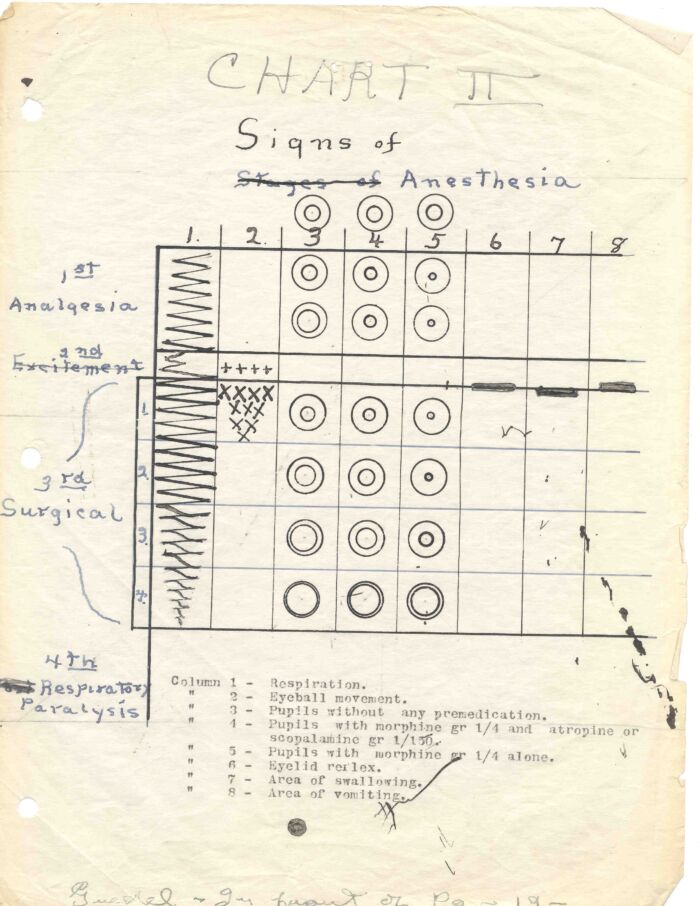

- Dr. Arthur Guedel served in World War I and helped train hospital personnel to safely administer anesthesia. Based upon this work, Dr. Guedel created a chart (Figure 1) that defined and characterized four stages of anesthesia as a means of evaluating anesthetic depth.1,3,4

- Guedel’s four stages of anesthesia were developed through observation of patients who received morphine and atropine premedication followed by the inhalational anesthetic ether in the 1910-1930s. Guedel’s stages continue to be referenced in modern anesthetic practice.3

- Although modern monitoring and gas analyzers have led some to question the usefulness of Guedel’s system today, it continues to provide a framework for clinical assessment of anesthetic depth.1

- Patients receiving modern volatile anesthetics alone continue to demonstrate the characteristics Guedel proposed for each stage of anesthesia (Table 1).3

- Patients receiving balanced anesthesia with intravenous anesthetics, analgesia, neuromuscular blockade alone or along with modern volatile anesthetics less reliably demonstrate Guedel’s characteristic clinical markers of each stage of anesthesia and may skip some stages altogether.1

Figure 1. Guedel’s Signs of Anesthesia Chart. Used with permission from UCSF Archives and Special Collections.

Stage 1: Analgesia

- Stage 1 of anesthetic depth, often referred to as the induction stage, begins with the first administration of any anesthetic drug and ends with the loss of consciousness.5

- During stage 1, the patient remains in a state of analgesia and disorientation with or without amnesia.

- Patients in stage 1 will demonstrate slow and regular respirations and should be able to maintain a conversation.5

Stage 2: Excitement/Delirium

- Stage 2 of anesthetic depth is characterized by the loss of consciousness and continues to the onset of autonomic breathing. Disinhibition, uncontrolled movement, and airway hypersensitivity are characteristics of stage 2.5

- Patients in stage 2 are at the highest risk of laryngospasm, and airway stimulation should be avoided.1

- Hypertension, tachycardia, irregular respiration, and nonpurposeful response to painful stimulus, may all indicate that a patient is in stage 2 of an anesthetic.5

- Eye examination during stage 2 is characterized by loss of the eyelash reflex, divergent gaze, and reflex pupillary dilatation.6

- Patients receiving a total intravenous anesthetic may exhibit fewer, if any, of the characteristic signs of stage 2 of anesthetic depth.

Stage 3: Surgical Anesthesia

- The resumption of regular, spontaneous respiration marks the entrance into stage 3 of anesthetic depth, which continues until respiratory paralysis.7

- Stage 3 is the depth of anesthesia that is most desirable for surgical incision.6

- During stage 3, airway reflexes become suppressed, allowing for safe airway manipulation, including insertion and removal of an endotracheal tube.7

- Stage 3 can be divided into 4 separate planes of anesthesia.7

- Plane I is marked by spontaneous breathing and central, constricted pupils with loss of the eyelid and conjunctival reflexes.5

- Plane II is characterized by intermittent cessation of respiration along with the loss of ocular movement and laryngeal reflexes.5

- Plane III is marked by the loss of function of the intercostal and abdominal musculature and the loss of the pupillary light reflex. Plane III is considered “true surgical anesthesia” and is ideal for most surgeries.5

- Plane IV is demonstrated by irregular respiration and, eventually, full diaphragm paralysis, resulting in apnea. The carinal reflex is also lost in plane IV of stage 3.3

Stage 4: Overdose

- Stage 4 of anesthetic depth is marked by apnea. Anesthetic overdose is the characteristic feature of stage 4.7

- During stage 4, the patient’s pupils become fixed and dilated, and all reflexes and skeletal muscle tone are lost. Hypotension and bradycardia can occur, indicating brainstem and cardiovascular suppression.7

- A patient in stage 4 should have anesthetic depth reduced as soon as possible or risk cardiovascular injury, neurologic injury, and death.7

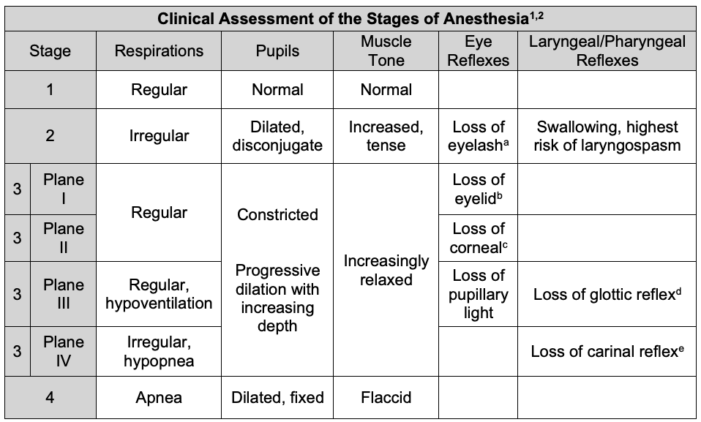

Table 1: Clinical assessment of the stages of anesthesia.

a The eyelash reflex results in blinking in response to gentle brushing of the eyelashes.

bThe eyelid reflex results in blinking in response to touching the medial canthus of the eye.

cThe corneal reflex results in blinking in response to light touch of the cornea.

dThe glottic reflex, also known as the laryngeal adductor reflex, results in glottic closure following laryngeal stimulation.8

eThe carinal reflex results in cough in response to lower tracheal and carinal stimulation.9

References

- Siddiqui BA, Kim PY. Anesthesia Stages. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Link

- Shepherd D. History of Anaesthesia: John Snow and Research. Can J Anaes.1989;36:2 224-41. PubMed

- Jones S, Cadogan M. Arthur Ernest Guedel. In: LITFL - Life in the FastLane, Accessed on August 31, 2023. Link

- Calmes S. Who was Dr. Arthur Guedel? UCSF Archives and Special Collections. Published June 5, 2015. Accessed November 8, 2023. Link

- Winterberg AV, Colella CL, Weber KA, et al. The child induction behavioral assessment tool: A tool to facilitate the electronic documentation of behavioral responses to anesthesia inductions. J Perianesth Nurs. 2018;33(3):296-303.e1. PubMed

- Freeman BS. Stages and signs of general anesthesia. In: Freeman BS, Berger JS. eds. Anesthesiology Core Review: Part One Basic Exam. McGraw Hill; 2014. Accessed October 2, 2023. Link

- Mayer S, Boyd J, Collins A, et al. Characterizing fentanyl-related overdoses and implications for overdose response: Findings from a rapid ethnographic study in Vancouver, Canada. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018; 193:69-74. PubMed

- 8. Domer AS, Kuhn MA, Belafsky PC. Neurophysiology and clinical implications of the laryngeal adductor reflex. Curr Otorhinolaryngol Rep. 2013. 1(3):178–82. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.